Olympic Games—Stockholm 1912

Images from the 1912 Games from the Harry Ross Soden collection can be found through this link at the Australian Rowing Images website.

If the Games of London finally produced a Games worthy of the title Olympic Games, Stockholm provided de Coubertin with the organisation and enchantment he had always sought. "We went to Stockholm as British athletes; we came home Olympians, disciples of the leader, de Coubertin, with a new vision which I never lost." Rt Hon Phillip Baker in the book The Olympic Games, edited by Lord Killanin and John Rodda. Australia and New Zealand competed for the second time as Australasia, but this was the last time.

The general manager of the team was Vicary Horniman. Harry Gordon included a passage on Vic Horniman in his book Australia and the Olympic Games as follows: "The manager of the 26 strong Australasian team to Stockholm was Vicary Horniman, a Sydney militia civil servant who had served as a captain in the New South Wales militia until 1901, but had retained his army title and a military looking moustache. He was a keen rower, but not a distinguished one, and had been active as a starter, judge and umpire with the New South Wales Association. His appointment in March 1912 was one of the first joint actions of the newly formed State Olympic councils. Although Horniman was unopposed, A G de L Arnold, who acted as coordinating secretary for the various Olympic bodies, was diplomatic enough to clear the appointment personally with Basil Parkinson in Melbourne before announcing it."

The proud history of rowers being the general manager/Chef de mission of Australian Olympic Teams had begun. Of the 25 General Managers/Chef de Missions for Australia at the Olympic Games, rowers have held this position on 9 occasions as at 2020.

Selection

As Rowing Australia Inc was not yet formed, this was a joint arrangement between the New South Wales and Victorian Rowing Associations. The selection committee for the eight comprised Alex Thompson (NSW) who assisted with the management of the eight, C S Cunningham (VIC) who travelled with the team and the coach Bill Middleton. The cost of the trip was estimated at £2,000 with about £600 expected to come from Victoria, principally from the wealthy Melbourne Amateur Regatta Association, the organisers of the Melbourne Henley Regatta.

In the end, £500 came from the Melbourne Amateur Regatta Association plus substantial donations from the families of the Victorian members, the Victorian Rowing Association President H Gyles Turner and the Athenaeum Club, totally in all £713.

It is interesting to note that alternative trips were considered such as a race against the English on the Zambesi. In the end, the long awaited opportunity to test the Australian skill, stamina and strength against the best from England the Americas and Europe swayed the decision to attend the Olympic Games. It is clear from the materials at the time that racing at the Henley Royal Regatta was highly regarded.

The Olympic crew, with one change (Hugh K Ward out and Keith Heritage in), won the Grand Challenge Cup at Henley Royal Regatta as Sydney Rowing Club. A squad of ten travelled to England but as A B Doyle (NSW) and Ward were already resident in England, the eight had a squad of 12 from whom to choose. Selection was controversial. Ward was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford at the time of the Games and joined the team in the UK for the Olympic Regatta. He competed for New College (Oxford) in the Grand Challenge Cup and so competed against his fellow crew mates in the semi final which was won by Sydney Rowing Club. He was not able to race for Sydney Rowing Club, having never been a member of it. His inclusion in the Olympic crew, at the expense of Keith Heritage, was criticized.

Harry Gordon in his book Australia at the Olympic Games states: "Afterwards Sporting Life expressed surprise that that the Australians had 'displaced a man who formed part of a machine-like crew, which was universally admired at Henley, for one who has assimilated the New College (Oxford) style of rowing'. George Towns, the sculler and boat builder, was also critical about the inclusion of Ward, who had stroked New South Wales to victory in the Australian Championships in 1910. "It is always dangerous . . . to alter a successful crew," he said. "The time was too short to allow of Ward becoming an 'Australian' rower again."

Training commenced in Sydney in 1912 when the two Victorians, Simon Fraser and Harry Ross-Soden arrived. With five members of the squad coming from Sydney Rowing Club, the other members joined the Club to enable an entry to be included in the Grand Challenge Cup event at Henley. The winning boat in the 1910 and 1911 Interstate Eights race, the Q L Deloitte, was packed up and dispatched overseas. A second and newer boat was also sent in case of damage. Finally, in April 1912, the R M S Osterley (the Royal mail ship) and the team left Sydney for London to a grand send off. McVilly joined the ship in Hobart. The team received great receptions in Hobart, Melbourne and Perth.

Cecil McVilly—Men's Single Sculler

The eight raced at Henley as Sydney Rowing Club with Heritage in and Ward out. They defeated the Argonauts crew from Canada in the first round by 1.25 lengths in 7:04. They defeated New College Oxford in the second round by a length in 7:10. Then, in the final, they defeated Leander in the Grand Challenge Cup before a crowd of 150,000 spectators. McVilly unfortunately was eliminated in the first round of the Diamond Sculls, one of the world's premier sculling events.

Other Racing

Men's Coxed Four

1st Germany (Ludwigshafen R V – Albert Arnheiter, Otto Fickeisen, Rudolf Fickeisen, Herman Wilker, Karl Leister (cox)), 6:59.4, 2nd UK (Thames), 3rd Norway. (11 crews from 9 nations – One history show Denmark 3rd and Norway 4th)

Men's Coxed Four – in riggers

1st Denmark (Nykjobing), 7:47.0, 2nd Sweden 7:56.2, 3rd Norway. (6 crews from 4 nations)

Gold Medal - Nykjobing Rowing Club from Denmark

Silver Medal -

Roddklubben Rowing Club from Sweden

Australian Team

Men's Single Scull - Disqualified for interference in his heat which he won

- Cecil McVilly (TAS)

Men's Eight - Eliminated in semi-finals

- Bow: John Ryrie (NSW)

- 2: Simon Fraser (VIC)

- 3: Hugh K Ward (NSW)

- 4: Thomas Parker (NSW)

- 5: Henry Hauenstein (NSW)

- 6: Sydney Middleton (NSW)

- 7: Harry Ross-Soden (VIC)

- Str: Roger Fitzhardinge (NSW)

- Cox: Robert Waley (NSW)

- Coach: Bill Middleton (NSW)

- Reserves: Stuart Amess (NSW) and Roy Barker (NSW)

Selectors: Alex Thompson (NSW), C S Cunningham(VIC), Bill Middleton (NSW)

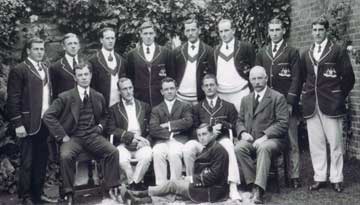

1912 Olympic Eight prior to departure to England for Henley and the Olympic Games

Standing: Stuart Amess (reserve), Simon Fraser (2), Keith Heritage (reserve), Thomas Parker (4), Henry Hauenstein (5), Sydney Middleton (6), John Ryrie (bow), Roy Barker (Reserve). Seated: Alex Thomson (manager), Roger Fitzhardinge (stroke), Bill Middleton (coach), Harry Ross-Soden (7), Charles S Cunningham (selector). In front: Robert Waley (cox). Missing: H K Ward and A B Doyle.

Racing

The races were conducted over 2000 metres which has been the standard distance for international rowing events for men since then. Women's events were originally conducted over 1000 metres but in 1988 were extended to 2000 metres.

Men's Eight

Olympic Racing - Heat: Australia defeated Sweden 6:57.4.

Semi: UK (Leander) defeated Australia (0.25 length)

Success at Henley against the Leander crew lifted the expectation of a good Olympic regatta. The Australian eight was one of the strongest crews of the Games and with better luck might have won the event. The official Report of the Games recorded their efforts in the following manner: "The perfectly trained visitors, who rowed like one man, took the lead at the 200 metres and never lost it. In the semi-final, Australia met the champion British number one eight from Leander. Australia led by 1.5 lengths at the 1000 metre mark but the British crew managed to catch them 100 metres from the finish. Regrettably the Australian crew had a sharp curve to negotiate at this point in the race which was a significant disadvantage." The British crew won by 3 metres and went on to win the gold with Australia eliminated. The race received due reference in the Official Report: "Those who had the pleasure of seeing this race will probably never forget it." Britain's time of 6 minutes 10 seconds was the fastest over the course. The race is noted in other publications as the highlight of the regatta.

Alan May in Sydney Rows reports: "On their return, many of the oarsmen ascribed their loss in the Olympics to their lane, Leander having 'well over a length's advantage'. According to Middleton, they could beat Leander nine times out of ten on a straight course. English rowing, generally, he said, "taught us little or nothing" regarding rowing or the fitting of racing boats. The accusation was also made that Leander failed to congratulate the Australians after the Henley success. These comments earned Middleton an English press description as "petulant and lacking in sportsmanship", while Horniman caused a stir by announcing that Middleton would be 'most severely censured' for his rude comments". A motion of disapproval before the NSWRA was, however, later defeated."

The silver medal winning New College eight from Great Britain contained Charles Littlejohn, a Victorian studying at Oxford and Beaufort Burdekin who was born in the UK to Australian parents. Stephen Cooper in his book ‘The Final Whistle: the Great War in Fifteen Players’ provides details on Burdekin and noted that he returned to Australia following WWI with his wife and children to practise as a barrister.

Final: 1st UK (Leander – Sidney Swann, Leslie Wormald, Ewart Horsfall, James Gillan, Arthur Garton, Alister Kirby, Phillip Fleming, Edgar R Burgess, Henry Wells (cox)) 6:15.0, 2nd UK (New College, Oxford - Sir William Parker, William Fison, Thomas Gillespie, Beaufort Burdekin, Frederick Pitman, Arthur Wiggins, Charles Littlejohn, Robert Bourne, cox: John Walker ) 6:19.0, 3rd Germany (Berliner Ruder Club). (11 crews from 7 nations)

Men's Single Scull

The Australian single sculler Cecil McVilly was a tall, muscular Tasmanian and the amateur sculling Champion of Australia. In the single scull he took the lead early but steered into his German opponent M Stahnke. The German was stopped momentarily but went on to complete the race. McVilly won by several lengths, but the judges were forced to disqualify him.

All finals comprised two crews only. It is suspected that the third placings were determined by the best other times in the semi finals. The only confirmation of this is a reference in Dr Ferenc Mezo's official history of the Olympic Games where he notes the English sculler Butler's entitlement to third placing in the single scull because of a faster semi final time over that of the Russian Kusik. This is however at odds with the fast semi final time of the Australians. Rowing representation had grown to 14 nations for these Games.

Sydney Middleton, later Major S A Middleton DSO OBE 1st AIF, rowed in the 6 seat and Harry Hauenstein, later Lt H Hauenstein, rowed in the five seat of the AIF No 1 crew which won the 1919 Peace Regatta race for the King's Cup. The King's Cup is now, and has since 1922, been the trophy for the Interstate Eights race.

Final: 1st William D Kinnear (UK) 7:47.6, 2nd Polydor Veirman (BEL) 7:56.0, 3rd E B Butler (CAN). However the Russian M Kusik is noted as the third place getter in the FISA Centenary Book. (13 scullers from 11 nations.)

Gold Medal - William D Kinnear (UK)

Bronze Medal - E B Butler (CAN)