History of Newcastle Rowing Club

Part 1 - Rowing in Colonial Australia (continued)

Part 1 pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Racing

Not everybody wins and certainly, nobody wins all the time. But once you get into your boat, tie into your shoes and bootstretchers then "lean on the oars" you're won far more than those who have never tried.

Anon

All rowed fast but none so fast as stroke.

from Sandfort of Morton

Desmond Coke

When boat racing came into general favour as. a sport in England early in the 19th century there were no rules, as such. Professional watermen on the Thames resorted to all sorts of unscrupulous tactics. Contestants negotiated how their race would be organised and what, if any, rules would apply so considerable latitude prevailed. Fouling was not necessarily disapproved of as it is now. In some quarters it was openly sanctioned. Among gentlemen however, rowing was no place for underhand behaviour. Anyway, there was more scope for that sort of stuff in their businesses. In 1848, amateur rules were defined to ban fouling under any circumstances.

As Australian rowing closely followed English practices, a similar attitude to racing applied to professional rowing here in Australia; initially anyway.

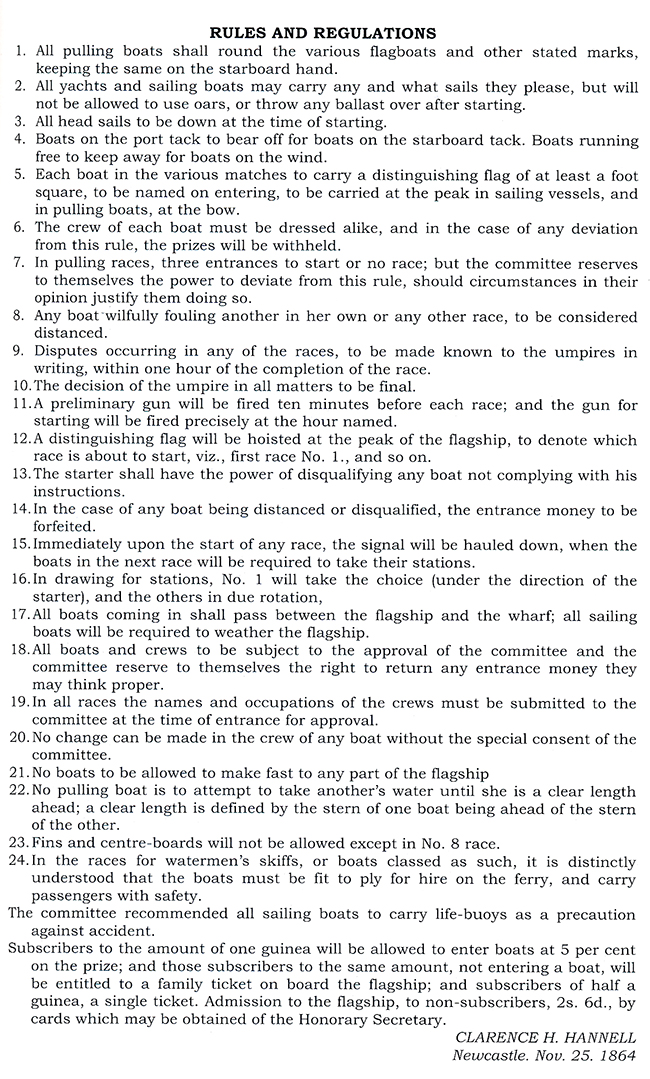

Organisers of local regattas had to adopt rules that could apply all classes of rower, professional, amateur, and manual labour amateur. Newcastle's Annual Regatta was no exception, adopting rules that were, almost certainly, based upon those used by established committees in Sydney. The following table is a facsimile of the rules and regulations for the 1865 NAR.

Apart from some relatively minor alterations, the rules applied at all NARs until they ceased in the 1900s. One change was a provision that competitors line up in order with the No 1 boat closest to the starter. Previously crews were able to choose their preferred position in order based on the boat number. Another was a requirement that any winner of a youth race supply a birth certificate.

Usually, boats were weighed by a sub-committee a day or so before a regatta to ensure that they complied with the class specified and to determine if any weight needed to be added to lighter boats to ensure parity.

Handicap races were common as they gave each crew an equal chance of winning and hopefully, resulted in close, exciting, finishes. Weights added (usually bags of sand) were normally between 10 and 50 lbs although the highest recorded in Newcastle was 190 lbs.

What appears to be an eminently sensible procedure was undermined if a crew tossed their weight(s) overboard. This lurk was thwarted by rules at some regattas (e.g. Hexham 1856; Newcastle 1865) that banned weights being jettisoned once the race had started. A tricky alternative to rectifying disparity between boats used in at least one regatta (West Maitland, 1863) was to handicap by adjusting the race distance for different boats.

Although weight handicaps persisted and were used at a regatta at Stockton as late as 1931, timing handicaps became more the norm from around the turn of the century led by the influential Balmain regatta committee that introduced handicapping by time instead of weight in the mid-1890s. This innovation was made possible by the increasing availability of standardized boats ..

Occasionally, organisers of some early regattas omitted to specify what rowers should wear or boats carry to identify them. Consequently, there were complaints from the public and judges unable to identify the crews or place getters. It was usual therefore to require rowers to wear a cap or clothing in distinguishing colours. In some instances, a 1 foot square coloured flag had to be mounted on the boat. In 1883 a regatta rule was introduced requiring all members of a crew pulling boats to be dressed alike and wearing a sash not less than 3" wide. Professional rowers wore their colours either on a cap or jersey. All this will seem obvious to today's competitors used to wearing club colours and carrying a lane number on the bow of their boat.

Rules for the conduct of all amateur racing were also developed in 1886 by the NSWRA. In brief, Rule 1 defined a public race. Rule 2 "did away with the absurdity of wearing sashes". Rule 7 provided for a boat "abiding by its own accidents". An umpire could order a rerun if the race was lost or boat disabled by interference. Rule 9 allowed choice of station to the No 1 boat. Rule 11 dealt with the course a boat should take on both straightaway courses and those with turns. Rule 10 covered wilful fouling caused by coxswains. The new rules also detailed the string test rule for gigs, and clarified specifications for several classes of boat.

1890 Regatta Regulations included many of the types of rules we are familiar with today. Several of the more interesting are no longer in use. One that is unlikely to upset modern rowers too much was the requirement for crew members to wear a guernsey with short sleeves, knickerbockers (reaching the knees) and stockings or socks. Others relate to races where a turn is to be made, namely:

"all boats shall round the various marks by keeping the same on the starboard [bow] side.

"a boat may take another boats water when a clear lengths lead has been secured. A clear length shall be defined by the stern of one boat being ahead of the stem of the other. No boat shall alter its course to prevent another boat from passing it on either side. A boat must not attempt to turn inside a leading boat, but must pass on the outside, unless the leading boat is less than a length ahead, when the inside boat is entitled to the turn." [Officials today will be relieved they don't have to adjudicate on this one.]

By the early 1900s, professional rowers were incorporating the NSWRA's rules of racing into Articles of Agreement covering their match races.

With enormous public interest in an ever increasing number of regattas, successive Colonial Governments found it necessary to gazette new regulations under the Navigation Act to control boat movements on waters for which they were responsible.

Newcastle's harbour, like Sydney's was an extremely busy, often congested, working port. On these and most waterways used for boat racing, even those regarded as championship courses such as the Hunter and Parramatta Rivers, there were constant complaints of interference on competing boats by a jostling spectator fleet, numerous following steamers and boats moored along the course. Obviously, this had the potential for conflicts ranging from interference to collisions.

Consequently, regulations under the Navigation Act were gazetted in 1877 by the Marine Board for the conduct of regattas and boat races. No boat was permitted to follow a race without prior approval of the Marine Board. Approved vessels were allotted a position in the following fleet and required to carry an identification number. All other craft on or along the course had to be anchored or stationary. No vessel could come within 300ft of a competing craft. The penalty provided was £10.

In 1879 additional Regulations were applied. They prescribed a clear mid-channel track not less than 300 ft wide the entire length of the course and only two steamers were allowed to follow any race, one for the press, the other for the umpire. Penalties for masters breaching the regulations were a fine of up to of £10 and possible cancellation or suspension of their license. Over the next few years, other regulations were added in response to to deal with issues as they emerged. For instance, the penalty was increased in 1881 to £100. In 1885 the number of steamers permitted to follow any race was reduced to one: authorised the Colonial Treasurer to designate courses for boat races and regattas in navigable waters: required that courses be kept clear during specified times and extended the penalties for breaching the regulations to include 'any person", not just those classified as masters or owners. In 1888 a new regulation restricted the speed of steamships on the Parramatta River course during boat racing to a maximum of six knots.

Race preparation was an increasingly important aspect of competition. One report revealed that "rowers prepared for their races with diets based on raw meat, uncooked eggs, beer and sherry with morning and afternoon rubs with a flesh brush as well as rowing practice".

A preparation more likely to be successful was followed by world champion sculler James Stanbury prior to his defence of the title against George Towns on the Parramatta River championship course in 1906. His daily exercise consisted of either a 4 mile walk or a 3 mile run before breakfast, a one hour rest then a 2-3 mile walk. At 11.00 am he rowed over the course. After lunch another one hour rest was followed by another 2-3 mile walk. At 4.00 pm he rowed the course once more, this time hard. Subsequently, he had a rub down, dinner at 6.00 pm, a walk of 6 miles then bed. On the other hand, it might have been more instructive to know Towns' training regimen. After all he won the race.

Of course, not all crews prepared so meticulously. This is exemplified by the more realistic if rustic approach by a local crew comprising Alex Ripley (s), Bill "Snowy" Fruend (3), Bert Ripley (2) Charlie Gordon (b) with young Andrew Ripley as cox. Assembling at Hexham in the 1920s prior to catching a steamer to Morpeth for the race they were asked what training they had done that morning, Alex and Bert said that they went for a casual run of about one mile. Charlie said that when he arrived at the wharf there was no boat so he stripped off and swam across, then had to row back to get his clothes. When asked, Snowy said "I milked 40 bloody cows then ran up here. Andrew piped up and said "and I milked the goat". It was a successful preparation. Some of the 100 pounds prize money (and betting money) went towards the purchase of bottles of rum and beer. Needless to say, there was much singing on the steamer back to Hexham afterwards.

If a fast boat and good preparation was not enough there is always the old waterman's advice of 1880 - "If you wants to win you must row your werry hardest and if that there don't do, clench your teeth and row harder".

Part 1 pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Previous < Introduction