Stuart A M Mackenzie

Sydney Rowing Club and Leichhardt Rowing Clubs (NSW)

April 4, 1936 - October 20, 2020

1955 – Interstate Men’s Eight Championship five seat – Third

1956 – Interstate Men’s Sculling Championship – First

1956 – Olympic Games – Men’s Single Scull – Silver

1957 – Interstate Men’s Sculling Championship – First

1957 – Henley Royal Diamond Sculls – First

1957 – European Championships – Single Scull – Gold

1958 – European Championships – Single Scull – Gold

1958 – British Empire & Commonwealth Games – Single Scull – Gold

1958 – British Empire & Commonwealth Games – Double Sculls - Silver

1958 – Henley Royal Diamond Sculls – First

1959 – European Championships – Single Scull - Fourth

1959 – Henley Royal Diamond Sculls – First

1960 – Henley Royal Diamond Sculls – First

1960 – Olympic Games – Single Scull – Did not race due to illness

1961 – Henley Royal Diamond Sculls - First

1962 – Henley Royal Regatta Diamond Sculls - First

1962 – World Championships – Single Scull representing UK – Silver

1969 – Interstate Men’s Sculling Championship – Fourth

1977 – Interstate Men’s Eight Championship coach – First

Stuart was an exceptional Sculler whose racing at Henley Royal is legendary. His story telling and the stories told of him, are very enjoyable. He is a colourful personality.

Stuart qualified for three sports for the 1956 Olympic Games, rowing, shooting and discuss.

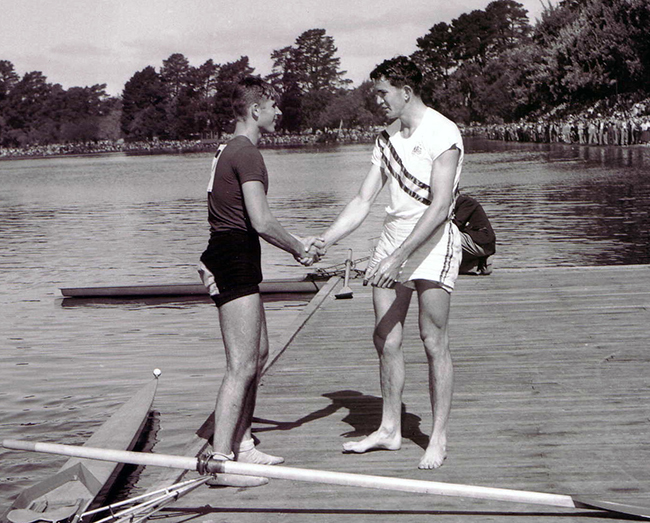

Mackenzie congratulates Ivanov after being beaten at the 1956 Olympic Games

Harry Gordon in his book Young Men in a Hurry published by Landsdowne Press in 1961, wrote the following essay on Mackenzie titled The Unquiet Australian which captures his essence very well.

Australia has produced three world-beating scullers, and two of them were barred for a time from competing at Henley because they weren't officially gentlemen. The other was Stuart Mackenzie, probably the beefiest, brashest, most confident and efficient practitioner of the sport never to have won an Olympic gold medal. He wasn't much of a gentleman, either, in the eyes of Henley officials. But he still became the second man in history to win the Henley Diamond Sculls five times in a row.

The Henley Royal Regatta, encrusted now with 122 years of history and tradition, never expected or deserved to see anyone quite like Stuart Mackenzie. It is a colorful period-piece in sport, a classic that is rowed on the lovely reaches of the Thames in the first week of July, against a background of punts, houseboats, candy-striped marquees, pretty girls in summer frocks, and young bloods addicted to strange boaters and ties the colours of king prawns. The fashions sometimes get out of hand, but rarely the cheering … most barrackers are satisfied to wave their boaters, hold pint pots aloft, and murmur, "Rowed, House", through fairly clenched teeth.

The Henley Regatta Committee, which went into business in 1839, clung for many years to Victorian definitions of amateurism. The word "amateur", French in origin, was first used in reference to aristocratic collectors and connoisseurs of the fine arts - and when it was applied to sport in the 19th century, the terms "amateur" and "gentleman" became interchangeable. So it was that the Regatta Committee, which became Royal and fashionable in 1851 when Prince Albert gave it his patronage, ruled that anyone who was "by trade or employment for wages a mechanic, artisan or laborer" was ineligible. In 1866 the Amateur Athletic Club did the same thing. Over the years this ruling bothered several people - among them J. B. Kelly, father of the well-known princess. The popular legend goes that young Kelly was barred from competing at Henley in the Grand Challenge Sculls in 1920, because he had once worked with his hands; it isn't true. In fact, although the "tradesman" definition was then in force, Kelly was thrown out because he represented a Philadelphia boat club which was excluded specifically from Henley on the grounds of "professionalism". Kelly, however, took the whole thing as a terrible slur on the American working man; boiling with Irish indignation, he went on to win the Olympic gold medal that year and then mail his perspiration-soaked rowing cap to King George V - a complete innocent in the case, who visited Henley only once in his life. The pay-off in the Kelly case came some years later, when John Kelly junior won the Diamond Sculls and daughter Grace became Royal herself.

The truth is that Australia's two Olympic sculling gold medallists, Bobby Pearce and Merv Wood, both had considerably more reason to feel angry towards Henley than John Kelly. In 1928 Pearce set a 2000-metre Olympic single sculling record on Holland's Sloten Canal, pausing only to shoo away a brood of ducklings which blocked his lane - but the same year he was ruled ineligible for Henley, because he was a carpenter. In the depression year of 1930 he was reduced to picking up scrap paper at the Sydney Showgrounds - but later in the same year he accepted an offer from Lord Dewar, the Scottish whisky tycoon, to become his Canadian sales representative.

Lord Dewar promptly nominated Pearce for Henley again, and this time, listed under the apparently more dignified occupation of whisky salesman, he was rated fit to contest the Diamond Sculls. He won the race by six lengths in 1931, and in 1932 won his second Olympic gold medal in the single sculls at Los Angeles. In 1933 he defeated England's Ted Phelps by 200 yards in a three-mile race to take the world's professional sculling title at Toronto. So great was Pearce that he dominated the world's professionals until the outbreak of the Second World War.

Merv Wood was not a sculler when he was barred from Henley. It happened in 1936 when he was a member of Australia's eightoared crew that competed in the Berlin Olympics. Because they were all policemen and therefore artisans, the entire crew was disqualified from competing at Henley. This regulation was amended the following year, and these days is open to carpenters, Russian corporals, dustmen and chicken-sexers alike. Wood, a fingerprint expert in Sydney's Criminal Investigation Bureau, switched to sculling after his return from Berlin, and in 1948 he beat the world's best amateurs in the single sculls at the London Olympic Games. That year he tackled the Henley Diamond Sculls for the first time, and won the race. He won the Henley classic again in 1952, but was beaten into second place in Helsinki by the Russian Turi Tjukalov. Wood made his fourth Olympic team in 1956, when he and another policeman, Murray Riley, won a bronze medal in the double sculls.

In Melbourne's Olympic year of 1956, Stuart Mackenzie was 19 years old, and not long out of Kings School, Parramatta (Sydney), where he had been a leading all-round athlete. The son of a prosperous poultry farmer, he had started work as a chicken-sexer and he was already very calculating and disarmingly sure of himself.

At Ballarat he and Merv Wood duelled for the Australian single sculls championship, each knowing that the winner would gain automatic Olympic selection. Wood was 39 and had competed in the Olympics a year before Mackenzie was born; he was almost over the international hill, but there was a great deal of public sympathy for him. This Mackenzie did not share; he indulged in fact in a good deal of prickling gamesmanship before the race, making no secret of the fact that he thought Wood was much too old to be a serious threat. To a schoolboy who was representing West Australia in the single sculls - and who represented no danger to either Mackenzie or Wood - he muttered fiercely and unnecessarily on the morning of the race: ''I'm going to kill you out there this afternoon."

I remember a press interview a day or so before which caused some disaffection between Mackenzie and both officials and newspapermen. He pointed out that he had been at the sport for only seven months. "I was rowing in the New South Wales King's Cup crew", he explained, "and I got to thinking about Merv Wood. It was obvious that he had just about had it, and nobody else much good was coming up. So I got out of the eight and decided to tackle the old bloke". He went on to explain that even if he didn't beat Wood he would gain Olympic selection in the double sculls, and that even if he had given sculling away completely, he would have made the Olympic track and field team. "I can throw a discus 140 feet", he said. "And 135 was good enough to win the Australian championship this year. I was going to have a go at the discus, but I reckon I won't have to now."

Mackenzie did not have to resort to the double sculls, or the discus. He beat Wood convincingly, gave him a perfunctory handshake, and went into the boatshed to conduct another press conference.

"That lad is too cocky for his own good", observed one official rather sadly. "He had a splendid opportunity to say something nice to Merv Wood after the race. Merv's been a great champion, and now it's all over. What we saw out there on the lake was the end of an era. And the kid's just taken it as a matter of course ... "

The kid has always taken most things as a matter of course. He is a strange mixture; boastful, extrovert, infuriating at times and thoroughly likeable at others. He says and does the wrong thing often, and is usually surprised to find out that he has. His boasts are big, but they are also authentic. The truth is that at 6 feet 4 inches and 14 stone, he is a superb physical specimen who could have reached world class at any one of half a dozen branches of sport. One quality he shares with Herb Elliott is his calculated, almost ruthless single-mindedness. And, like Elliott, he is very jealous of his record over his pet event; if he can't do his best, he'd rather not compete.

Mackenzie was a strong lad in 1956, but he lacked the guile and experience of his opponents. He was beaten into second place in the Olympic final by the Russian Vyascheslav Ivanov, but he defeated John Kelly, junior, who wound up his single sculls career with a bronze medal. Soon after he took off for England, explaining with characteristic modesty: "All I need is some real competition, and I won't get it here. With a little knowhow, I reckon I can beat this bloke Ivanov." He was not going to neglect the chicken-sexing side of his career, either; when he wasn't sculling, he intended to study poultry diseases.

In Britain, Mackenzie quickly established himself as the strongest sculler in the world, and also the most controversial character on the Thames. He won the 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960 and 1961 Diamond Sculls and the 1957 and 1958 European championship, humbling his Olympic conqueror Ivanov several times in the process. By winning the coveted Diamond Sculls five times in a row he equalled the record of the Englishman J. Lowndes, who won from 1879 to 1883. He also managed to shatter most of the local conventions, was rebuked by officials and even booed by the normally sedate Henley crowd. He did this because he is one of those Australians who become more brashly, assertively Australian when they go abroad. His reaction to the "old boy" stuffiness of the English rowing world was to show off outrageously; he got a tremendous kick out of startling the natives. Once he wore a bowler hat as he sculled, and on another occasion he pulled up half way through a race and adjusted his cap while his opponent caught up-then pulled ahead to win easily.

Several times he argued with pressmen and heckled officials during races - and once, particularly irate, he took time out to paddle across to a launch and splash a passenger who had been calling him some unkind names. Of course, he went on to win the race.

He practised gamesmanship unashamedly, and generally appeared to enjoy himself immensely every time he went on the river. This, to Englishmen dedicated to the proposition of competing and, let's face it, losing earnestly and sportingly, was a very bad show indeed.

In 1957, not long after his arrival in Britain, Mackenzie demonstrated that he was fast gaining the experience which had missed so much at the 1956 Games. A couple of days before the Diamond Sculls he agreed to a training row against Ivanov, who was also competing at Henley for the first time. While the Russian coaches, armed with stopwatches, studied their form, the two crack scullers pulled stroke for stroke for a few hundred yards; then Mackenzie dropped back several lengths behind, and he was slumped forward over his oars, well beaten, as he reached the finish. Ivanov roared elatedly and slapped the sides of his boat, and afterwards Mackenzie explained straightfacedly to the press: 'I’m ashamed. He was too good for me - too fit, too fast."

Certainly the work-out lulled the Russians into a considerable sense of security-but several discerning English critics wondered whether the Australian had really been flat out. In fact, he hadn't; and two days later Mackenzie became the virtual world champion by downing the Olympic gold-medallist by four feet. After the race several critics accused Mackenzie of questionable tactics in forcing the Russian into the boom lining the course, thus giving him no opportunity of overtaking. The Russians considered lodging a protest, but decided against this action, since there had been no direct interference.

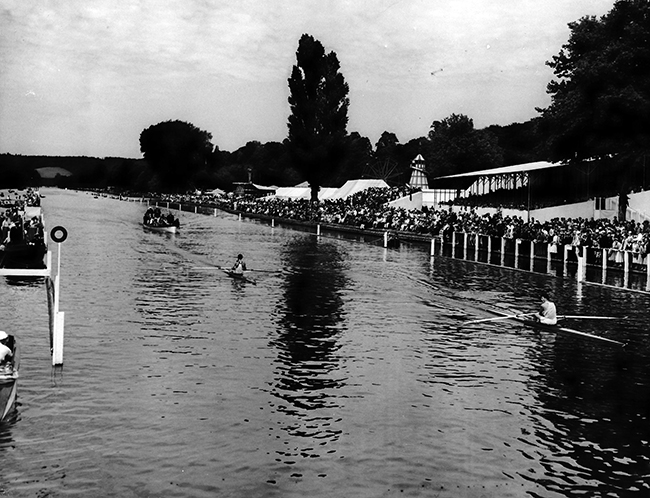

Mackenzie cruising to the finish line in a heat of the Diamond Sculls in 1957 defeating S C Rand of Henley RC

Mackenzie defended his tactics heatedly. "Sure I gave him my wash", he said. "That was how I planned it. I know these Russians. If you let them get in front of you, they give you their wash. All I did was play it their way. I got away fast and crossed into the middle of the river. I got a few warnings from officials, but I didn't actually hit Ivanov, so there can't be any question of disqualification. You have to remember ... sculling's a matter of tactics, like, say, bike riding." And that was that.

Later in 1957 Mackenzie showed the critics that his win against the Russian Master of Sport had been neither a fluke nor simply the result of giving him his wash. He won the European title at Duisburg, Germany, skimming over the 2000-metres course nine seconds faster than Bobby Pearce had done in the 1928 Olympics at Amsterdam.

Significantly, by the time the 1958 Diamond Sculls arrived, the regatta rules had been altered drastically. So much controversy had surrounded the giant Australian's win the previous year that any rower moving into an opponent's lane, even when well ahead, would now be automatically disqualified. It made little difference; he beat the Russian by 20 lengths, but still managed to have himself hooted (rather politely, of course) and accused by some of the starchier critics of "bad form". He raised his cap, while still contesting the race, and nodded genially to the crowd on the lawns. Taxed about this behaviour later, Mackenzie retorted: "You can call it swank if you want to ... actually I was just being polite."

In the final the red-vested Russian led at the halfway mark - to which point both had equalled the 28-year-old record for the distance - but he folded up soon after. Then Mackenzie cut loose with superb power and style, and his bulky blue singlet went farther and farther away. Yards before he reached the winning post the Australian had stopped sculling to glide home - and as he passed the press box he could be heard bellowing to the occupants: "Sorry I couldn't do any better, boys ... I've got a bad back." Having passed the line, he promptly turned round and sculled back about 50 yards along the course, bobbing and grinning to fans and officials-most of whom gazed on stonily. This victory row was construed by rowing writers as a "typically flamboyant Mackenzie gesture", and it was certainly quite unprecedented at Henley. But when I asked him about it a few days later, he explained: "Look, all I wanted to do was shake hands with that poor bloke Ivanov. He was feeling pretty bad."

Mackenzie went on later that month to win the Empire Games single sculls at Cardiff and a month later defended his European title successfully; then he announced that he would stay in England to try to equal the record of Jack Beresford (Britain), who won the Diamond Sculls in 1924, 1925, and 1926. This he did quite efficiently in July, 1959 - and he was once again booed for his trouble. His offence this time was to slow down to a paddle after seeing that he had beaten the American entrant, Harry Parker. This time he carved himself another small chunk of history by becoming the first sculler ever to win both the singles and doubles sculls at Henley. He followed up the victory over Parker by teaming with the former Oxford Blue Christopher Davidge to take the doubles.

Mackenzie attained rare distinction that summer; he was the only one of 800 competitors at the Marlow Regatta who turned up incorrectly attired. Everyone else was immaculate, in shorts and club singlets, but Mackenzie chose to scull in blue tracksuit trousers and a singlet. "Mackenzie's clothes are a disgrace", announced the regatta secretary. "The Amateur Rowing Association lays down quite clearly that all oarsmen must wear shorts in their boats." Mackenzie, called to the office, insisted that he had every right to wear the trousers. "I was only rowing to the start", he said. "It's pretty cold, and I didn't want to run the risk of catching a chill "

Then, bowing to officials and removing his tracksuit trousers, he went out and won the Grand Challenge Cup by four lengths.

Mackenzie was never one of the favourite sons of the Marlow Regatta. It was there, the previous year, that he had paddled across to a launch and splashed an occupant who had been barracking him.

By now this most unquiet Australian had become a legend of sorts. In the exclusive Leander Rowing Club he made a habit of calling a viscount fellow-member "cobber", and was heard more than once to bellow encouragingly, "Good on yer, Dig" to an earnest earl. The Daily Express rowing writer was moved to describe him as "the most infuriating ... most inspiring competitor ever to reduce England to boy-size", and he noted that Mackenzie had begun to conform with tradition ... "with amused tolerance". "Today he finds us quaint, and rather endearing, like an eccentric aunt", the writer observed. The Daily Mail, dubbing him Henley's outstanding personality, had this to say: "His critics brand him 'no gentleman' - but his supporters regard him as a breath of fresh air at too-stuffy Henley, a gay personality, an entertainer."

In July, 1959, while holidaying and training in the Slovenian resort of Bled, Mackenzie was rushed to a Yugoslav hospital to undergo an emergency operation for a perforated stomach ulcer. The operation was a complete success, and Mackenzie announced afterwards that he would not race or train again that year - but would definitely be fit to scull for Australia in the 1960 Olympics. Less than a month later he changed his mind; he turned up in Macon, Central France, to compete in the European championships. Many of his friends considered that he was taking too great a risk so soon after a major operation, but Mackenzie was adamant. "I've given it a lot of thought", he said. "I hope to become the first man in history to win the European title three times in a row ... I've been in training for a fortnight, and there is no pain any more."

He was almost a stone underweight, and it was obvious that his decision was risky, courageous, foolhardy and thoroughly ambitious. In the final he led for most of the 2000 metres, but wilted badly towards the finish to be beaten into fourth place by his old rival, Ivanov. He had missed out on a unique hat-trick of Henley and European championships, and, as later events proved, the Olympic Games.

After Mackenzie won his fourth Diamond Sculls at Henley, and then the South African championship in 1960, it was generally assumed that he was quite fit again. He was rated, along with Herb Elliott and Dawn Fraser, as one of Australia's most certain gold medallists for the Rome Games. This mood of rosy optimism did not last long, however. Soon reports began to filter back to Australia, through all the wrong channels, that he might be unfit to compete.

It was a landlady near Como, of all people, who unleashed to the British press the news that Mackenzie felt that a recurrence of his ulcer trouble would make it impossible for him to race. He was driving, at the time, in his blue Austin Healey across the Continent to Rome - and he seemed to be issuing bulletins along the way. From Lucerne, his mother, who had been visiting Stuart, telephoned her husband in Australia to say: "The boy will never row again. There is no chance of him competing in Rome." Then Mackenzie cabled his father to say: "No start. Please don't come to Rome. Will go to Japan 1964 together." He followed this information up with a letter, explaining that he was suffering from another stomach ulcer, and liver trouble. "I have kept this quiet because I hoped it would clear up", he wrote. "But I can assure you that unless I am thoroughly fit to row in Rome, I will not be a competitor at the Games."

As the European Press aired each new report, Australian officials who had already arrived in Rome became, with some justification, fairly upset. "It seems he's told everyone about his condition but the Australian team management", said an aggrieved Mr. Jack Howson, who was acting as advance manager of the team in Rome. "In the absence of any official word from Mackenzie, we have to presume that he is completely fit." And he pointed out reasonably: "We can't really ask the authorities to send a replacement simply on the say-so of a Swiss landlady."

I had lunch with Mackenzie an hour or so after he reached Rome. He was thoroughly preoccupied with his health, but as assertive and confident as ever. "I feel good, but I'm still doubtful", he said and I got the impression, maybe unfairly, that he was rather enjoying the limelight . . . that he would delay a decision, either through gamesmanship or sheer affection for publicity, as long as he could. "A new ulcer's formed, and there's only one way to stop it", he said. "That's with an operation. I've also got a bad liver, and I recently lost 40 per cent of my blood." Then he pointed out that even if he didn't row, he would like to carry the Australian flag -"I've got the physique for it, and a pretty good record" - and that he was thinking of taking on professional golf -''I'm a scratch man ... I played with Locke and Player in South Africa, and I reckon that with practice I could play as well as Player". Did he think he would win the Olympic title if he were fit, ... "Of course. I'd be quite confident of beating Ivanov or anyone else. The Russian hasn't improved in the last three years, and I've got steadily stronger and fitter. Even if I were 90 per cent fit, I'd still expect to win."

After this rather characteristic conversation, Mackenzie talked freely to Pressmen about Australia's other rowing prospects. It seemed that he was the only Australian oarsman who had any hope, and that rowing officials in Australia didn't know what they were talking about. "They skite in Australia about the fact that they're likely to get into every final, but they have a completely false impression of standards overseas ... I've already written to Australia telling officials who will get into the finals, and who'll finish first, second and third." In fact Mackenzie's assessment was accurate; Australian oarsmen qualified for only one final on Lake Albano, and did not win a single medal. But to issue such a forecast to a bunch of reporters before the Australian rowing team had even reached Rome was little short of foolish; it benefited neither the team's morale nor Mackenzie's personal popularity.

In other ways during those early days in Rome, Mackenzie did little to endear himself to either officials or the Press. Unable to train, he devoted much of his abundant energy to the pursuit of a series of rather tasteless practical jokes. After he made one straightfaced but false report about an Australian boat being damaged, team officials made an unnecessary trip to Naples. Then he told British Pressmen that an American and a Russian athlete had had a fist fight in the Village; most of them wasted several hours trying to check the story, which was of course baseless. Another of his more mischievous efforts was the circulation of a story that a bus containing Israeli contestants had been involved in an accident - and that several of the occupants had been badly injured. There was no truth in this either. Because the handling of news in the Olympic Village was so poor, every news tip called for careful checking - and all of these efforts, which Mackenzie regarded as vastly funny, involved newspapermen in large slabs of wasted effort. More than anything else, they revealed Mackenzie's determination to be a character ... a hero of anecdotes.

The will he?-won't he? Mackenzie farce continued until it was too late for officials to consider nominating another Australian for the single sculls. At one stage he told the team manager, Mr. Syd Grange, that he had been advised by a doctor not to go near the water until the result of a blood test and an X-ray were known but later the same day he was seen sculling on Lake Albano, and still later he admitted that he had not even undergone a blood test or an X-ray. Finally he announced that he would not compete in the Olympics ... a statement which brought this reply from the long-suffering Mr. Grange: "He's tried my patience too far. I'm accepting nothing the man says until I've had a doctor examine him."

It was not until two days before the Games began that Mr. Grange was able to announce what could presumably have been established weeks before: Mackenzie was suffering from a form of anaemia, and because of this and other factors, an ulcer specialist had reported that it would be most unwise for him to take part in the Games. "I should add", added Mr. Grange sadly, "that it is doubtful whether Mackenzie will ever compete again. He is a misunderstood young man in many ways, and I feel rather sorry for him."

A week later Ivanov, the man Mackenzie had whipped by 22 lengths at Henley, went on to win his second Olympic gold medal. Even he agreed that he was a very lucky Russian.

The Mackenzie story seemed likely to end there - with him established as the finest sculler in the world, but unable to prove the fact in the Olympics. But it didn't. Nine months after the announcement that he would probably never scull again, Mackenzie went out and won the senior sculls title at Putney. "I feel tremendous", he said - and began to train for his fifth Diamond Sculls.

In his semi-final of the big race at Henley, against fellow Australian Ian Tutty, Mackenzie rowed such a strange race that many critics were still doubtful about his fitness. Apparently playing cat and mouse, he continually baulked Tutty - and at one stage slowed up suddenly after taking his water, so that Tutty almost collided with his shell. For this he was cautioned by officials. He won by only a third of a length and afterwards Tutty was most upset, which is not unusual for Mackenzie's opponents. "If it had happened in Australia", he said, "Mackenzie would have been disqualified. He had me beaten, but he just wanted to show off."

Next day Mackenzie outclassed the Russian Oleg Tjurin, who had replaced Ivanov as Russia's number one, to win the final and equal Lowndes' 78-year-old record of five straight Diamond Sculls victories.

There was no doubt now that he was the outstanding sculler in the world - even of modern times -and the only thing which could prevent him remaining so for several years was his suspect fitness. Told by Australian officials that he would have to return to Australia to take part in test races before the 1962 Empire Games, he promptly, and rightly, refused. It was ludicrous that Mackenzie should be expected to prove himself against mediocre opposition in Australia before being allowed to represent his country in the Perth Games.

Then he suggested that if Australian officialdom continued to act so ham-handedly, he might be forced to represent Britain, and not Australia, in Perth. "At least with the British officials", he said, "a man knows here he stands".

Stuart Mackenzie was obviously enjoying himself. He was in the business again of keeping everyone guessing. And this, as officials and opponents across the world can testify, is something he does devilishly well.

Mackenzie was the guest speaker at a Rowing Australia luncheon in 2018 at Australia House in London and his stories and his personality were displayed to the delight of all present. He has no changed in all those years.

Andrew Guerin

May 2020

The following obituary was written by Pelham Higgins, a nephew of Stuart Mackenzie, and published in The Age on 30th November 2020. It is reproduced with the permission of Pelham.

Australian legend remembered as sculling great

By Pelham Higgins

Stuart Mackenzie April 4, 1936-October 20, 2020

Stuart Alexander Mackenzie, Olympic medallist and winner of a record-breaking six consecutive diamond sculls at Henley Royal Regatta, died on October 20, 2020, in Somerset, England. He was accompanied for the last 27 years of his life by his loyal and thoughtful wife Heather.

Regarded by many as the greatest single sculler of his time and probably Australia’s best sculler, “Sam” was “the beefiest, brashest, most confident and efficient practitioner of the sport never to have won an Olympic gold medal”, according to Harry Gordon (Young Men in a Hurry, 1961).

Even his greatest rival, three-time Olympic gold medallist Vyacheslav Ivanov, felt he was a lucky Russian when Sam stopped prematurely in the final of the 1956 Olympics and four years later had to withdraw from the Rome Olympics due to a stomach haemorrhage. Such was the admiration he had for Sam that in a recent message to Heather, Ivanov asked that his “sincere condolences be sent to the family of his closest foreign friend, the great sculler and champion Stuart Mackenzie”. Until the last years of his life Sam’s stories and legendary personality always delighted those present.

Much has been written about his rowing achievements and well-known gamesmanship, such as the superb recent pieces by Tim Koch and Chris Dodd (https://heartheboatsing.com/), but comparatively little is known about the man behind this often-misunderstood character - and most importantly the special people around him during both his formative and final years.

Sam Mackenzie, with his archrival and lifelong friend, triple Olympic champion Vyacheslav Ivanov (circa. 1960).

Sam was born at Malabar Private Hospital in Sydney, Australia, on April 4, 1936, to a prosperous and warm-hearted poultry farmer, Alan Alexander Mackenzie, and his uncompromising opera-singing wife, Phyllis Mavis Blanche Dearman. Hardened by World War I and subsequent Great Depression, Sam’s parents would go on to successfully raise him and his two highly intelligent and equally energetic sisters, Margaret and Diana, during another global conflict that ravaged Australia and the Empire. Margaret, Diana and Sam’s tough rural lives revolved around farming, animals, music and sports. The love for dogs that Sam learnt on A.A. Mackenzie’s Seven Hills property continued throughout his life with Oz by his side until the end.

Sam started schooling at Seven Hills Primary and was later enrolled as a day boy at The King’s School, Parramatta, in 1948 while his sisters attended Abbotsleigh. These would not only be some of the happiest days of his life but also very much the making of the man. He would become a boarder in 1953 as his rowing commitments increased and subsequently became house captain of Junior Macarthur house in 1954.

One of the most amusing stories of Sam’s school days was that he used to delight in telling all his mates that he was a “chicken sexer” – even though it was entirely true! In fact, many from his year have recounted this story more than once since his passing.

According to those who were at The King’s School with Sam, he was reputed for his kindness towards younger students. On one occasion during a mathematics class the over-exuberant teacher became enraged at one small lad who was defenceless and advanced on him to do harm. Just as the teacher reached the front row where the small lad sat, a towering figure stood behind the young boy – it was Sam who told the teacher “if you want to hit someone, here I am - just try your luck!"

The dedication and discipline that he demonstrated to his international rowing career appears to have not only been nurtured by his strict upbringing but also via The King’s School Cadet Corps. Sam was drum major holding the rank of cadet under officer and led the Band for Cadet Parades as well as the Sydney Anzac Day march. While his academic results were modest, his strongest subject was apparently Latin given the positive influence of The King’s School classics teacher at the time. Sam’s talents as a sportsman at The King’s School were nothing short of phenomenal.

He received full colours three times for athletics and shooting, and twice for rugby & rowing, and according to the school Archivist of Australia’s oldest school “there would have been very few boys who achieved 10 sets of Full Colours while they were at school!” Soon after leaving The King’s School, Sam qualified for the Australia Olympic rowing team in 1956 and, remarkably, also qualified for two other sports (athletics and shooting). His remarkable rowing achievements include an Olympic silver medal, six Diamond Sculls at Henley Royal Regatta, Commonwealth, European and World Championship medals.

However, as we were all reminded when he was laid to rest to the sound of Frank Sinatra’s My Way, Sam left this world with regrets which he very sadly rarely voiced. The biggest of these was having neglected his three children Rebecca, Alistair and Rachael – something that he reflected on more than once with his nephew, Pelham Higgins, who he was in regular contact with since 2001. The other regret was becoming estranged from his two sisters – especially Pelham’s mother Diana with whom he once had an exceptionally close relationship. Those who remember this special sibling bond often recounted how “she was his shadow and absolutely idolised him”. Pelham was particularly conscious of the relationship between his mother and her brother because each time they spoke Sam would always open the conversation with the words: “how’s your mum?”

And so, as Sinatra guides us to the final closing and this giant enigma of Australian sport leaves us all to stroke the ripples of the River Thames in front of his beloved Leander Club for one last time, it is only fitting that Rebecca, Alistair, Rachael, Margaret, Diana and Heather should be reminded that you can rest with the knowledge that behind Sam’s stubborn veneer you were all loved by a legend.

Vale Stuart Alexander Mackenzie. Husband, father, grandfather, brother, uncle and friend.

Pelham Higgins is Stuart Mackenzie’s nephew.

Roy Bishop, a fellow primary school student with Mackenzie at the Meadows Public School at Seven Hills where both attended primary school added the following story. Yes he was a big boy even then - we made a special rule for our school lunch time rugby - Makka (Stuart) wasn't allowed to score goals. He could run the ball to within 20 meters of touch and then he had to pass the ball; too big to tackle and bring down.

Compiled by Andrew Guerin

Updated 30th November 2020 and again in August 2024.