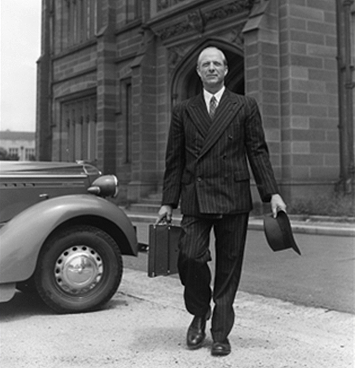

Prof Frank Cotton

The following rower profile of Professor Frank Cotton has kindly been provided by Ian Stewart.

Professor Frank Cotton - Pioneering Sports Physiologist

The father of sports medicine in Australia, in its broadest sense, was Frank Cotton, a former swimmer who became head of the department of physiology at Sydney University. He just missed selection in the Australian 4 x 200 metres freestyle relay team which went to the 1924 Olympics (and finished with a silver medal). He made major contributions during the 1940s and 1950s to the scientific knowledge of human physical performance, particularly in the fields of swimming and rowing, and died in 1955, a year before the Olympics in which his test-tube approach to training paid handsome dividends for Australia in the swimming pool.

Harry Gordon, “Australia at the Olympic Games”, University of Queensland Press, 1994. p. 266

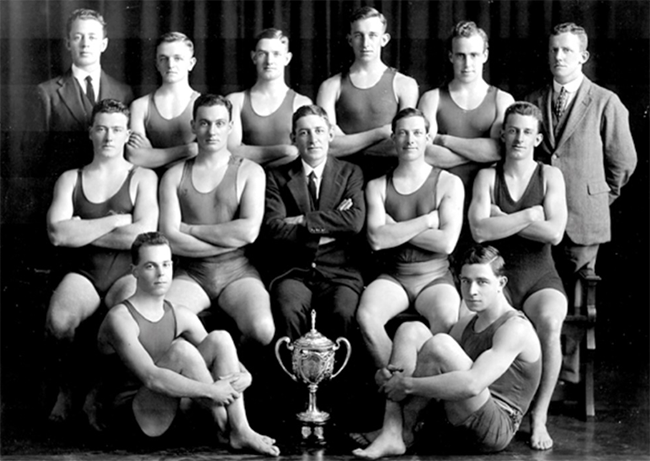

Sydney University Swimming Team 1920-21. Frank Cotton 2nd row 2nd from right

Frank Stanley Cotton was born in Sydney in 1890. He was educated at Sydney High School and later at Sydney University where he gained his BSc in 1912. Cotton was an elite swimmer as a young man. He won a University Blue for swimming and was NSW champion at 440 & 880 yards in 1921.

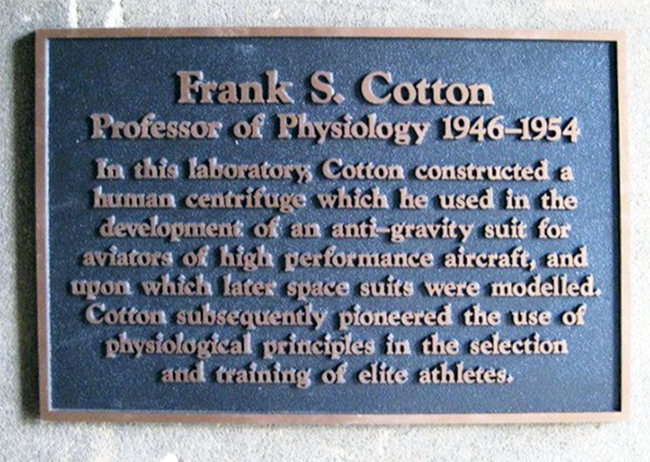

In 1913 he joined the staff of the University of Sydney’s Department of Physiology, becoming research professor in 1941 and full professor in 1946, a position he held until his death at the age of 65 in 1955.

His father was the Australian politician Francis Cotton (1857–1942) who played a key role in the rise of the Labour movement. He was the younger brother of Shackleton expeditioner and geology professor, Leo Arthur Cotton (1883–1963). Pioneer art photographer Olive Cotton was his niece. He attended Sydney Boys High School from 1904 to 1908.

In 1917, Cotton married Catherine Drummond Smith, a geology demonstrator who taught at the University of Sydney.

*

Almost from the time of his appointment to the Department of Physiology in the University of Sydney Medical School, Frank Cotton became interested in exercise physiology. It was from this preliminary experimentation that grew his direct involvement with the performance of athletes. Work output and its measurement was the beginning of a long connection with the measurement of human performance and a fruitful association with swimmers, rowers and track athletes up to elite level.

Before the Second World War athletes competing at international level trained according to schedules laid down often many years before, and by organisers who paid little or no attention to the detail of performance assessment. One trained by following one’s set pattern day after day, carrying out repeatedly one’s particular event, be it a sprint, a middle- or long-distance run, a swim of a particular distance or a 2000 metre rowing course. Technique was watched and corrected by coaches who held a book in one hand and a megaphone in the other. Scouts sought and found native talent in schools, universities and other local venues. This talent entered athletic squads, learned the technique and followed the set training tasks. Overall, it was as much a matter of luck and the possession of superior raw talent that finally won the day. One only has to look at the performances of Jesse Jackson, the American Olympic sprint star of the Berlin Olympics of 1936, to be convinced that raw talent combined with determination went a long way in the achievement of success.

There are three areas of Cotton’s interest to consider when it comes to athletic endeavour: track running, swimming, and rowing. In all three, Cotton, along with his senior lecturer, Forbes Carlisle, assessed and promoted the selection of internationally competitive athletes in all three sports.

It is of interest to look at Australia’s results at Olympic level from 1920 to 1936. In track running there was but one medal – silver – in 1920 in the 3000m men’s walk. Rowing produced gold medals in the single sculls in 1928 and 1932. The competitor was the phenomenal Bobby Pearce who came from a family of sporting giants. Included among these were Pearce’s grandfather and father, both Australian sculling champions. A cousin, Cecil, represented Australia in sculling at the 1936 Olympics. Cecil’s son, Gary, has rowed for Australia in the Olympics in 1964 (double scull), ’68 & ’72 (eight), the ’68 VIII gaining a silver medal. There have been other elite representatives from the family – in swimming and rugby league. This is mentioned to suggest that Bobby Pearce was, like Jesse Owens in 1936, a natural athlete for whom almost any training regime would be productive. There were better results in swimming with Sir Frank Beaurepaire winning bronze in the 1500m in ‘20 & ’24, at the end of a long career of elite level swimming, Andrew ‘Boy’ Charlton won four medals, including one gold, in 1924 and 1928. There were other swimming medals in 1932.

While the details of the above athletes’ training programs has not been studied, the list suggests that our Olympic success in these years was largely due to especially talented natural athletes rather than sportsmen and women whose success came from careful grooming via scientifically based training programs.

Enter Professor Frank Cotton.

By 1932, Cotton’s interest in cardiovascular responses to exercise had led him to begin to measure, in the field, the pulse-rate responses of athletes competing in their events. Through these investigations he discovered the post-exercise “pulse trough” which was common to almost all trained athletes. That year he was awarded the Rockefeller Travelling Fellowship and spent eighteen months in the USA in physiology departments which shared his interests in cardiovascular responses to stress.

One area of particular concern to Cotton was the effect of gravitational force variations on aspects of cardiovascular responses. This led him to address the question of fighter pilots blacking out during tight high-speed manoeuvres when the gravitational forces were exaggerated. Out of this came his invention of the anti-gravitation suit which became standard equipment for such pilots during WWII and which was taken up enthusiastically by the USAF. It is credited with having saved many pilots lives during this conflict.

Cotton began to experiment with the measurement of work output during the 1930s, using his departmental facilities to construct and further develop the work-measuring machines he called ‘ergometers’. When WWII intervened his direction temporarily changed but remained generally in the area of human cardio-vascular physiology.

Once the War was over and the centrifuge experiments had finished Cotton returned to his interest in exercise physiology. As Professor in the Department, he was able to co-opt one of the lecturers, Forbes Carlile, to work with him on the project.

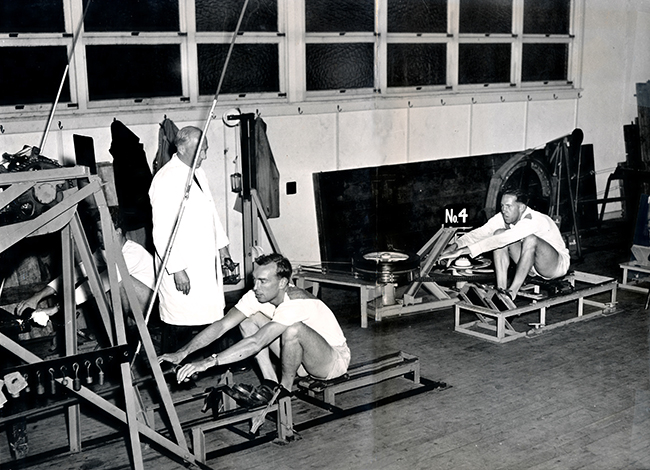

Cotton was able to redirect his enquiries to the cardiovascular responses of athletes. Investigation in the field was supplemented by measurements in his department’s laboratory. It was here that he devised what he called the ‘ergometer’ for measuring work output by subjects under controlled conditions. There were three variations of the ergometer that he had constructed in the late 1940s. One was a standard bicycle with a flywheel around which was a leather belt, the degree of frictional resistance being applied by weights attached to each end of the belt. The amount of weight to be applied depended on the weight of the subject being tested.

Two varieties of rowing ergometer were made. One had a vertical flywheel and friction belt to which weights were applied as with the bicycle type. The flywheel was set in motion by the athlete moving up and down the ‘slide’ on a seat like the one in the rowing shell and pulling on a handle rather like an old-fashioned lawnmower handle. This was attached by a system of levers to the flywheel. The athlete was instructed to quickly achieve a certain flywheel speed and then maintain it for the duration of the test.

As well as this type of rowing ergometer there was a pair of horizontal machines which had oar handles attached. One machine was for bowside oarsmen; the other was for stroke side.

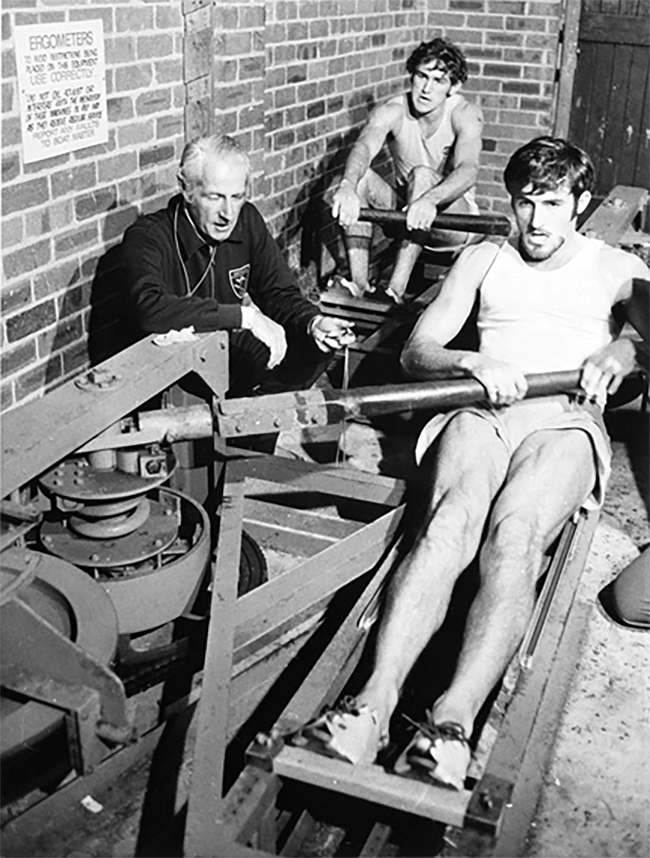

In this photograph, taken in Cotton’s Sydney University laboratory, one can see both types of ergometer.

The oarsman next to the number 4 is using the lateral-action type, while the other, Peter Evatt, is working with the vertical version.

E.R. Trethewie, of the University of Melbourne Department of Physiology, wrote to Cotton on10 April 1942 requesting details of a bicycle ergometer, having heard about it from a paper Cotton had delivered at Canberra in 1939.

Cotton replied: The model of bicycle ergometer we copied was the Martin Bicycle Ergograph described in ‘Proceedings of the Physiological Society’, February 14th, 1914…

This reference helps to time Cotton’s interest in the development of an ergometer for the measurement of human work output.

While most of the early examples of what came to be know as ergometers were of the bicycle type, Cotton developed two different rowing ergometers. John Harrison was one of Cotton’s recruits. Harrison was a fine athlete, with experience in surf boat rowing. He was an engineering student when cotton recruited him, Harrison’s interest having been lit by one of his university friends who knew of Cotton’s experiments. Harrison went on to complete a PhD in the engineering aspects of ergometry. The thesis is in the library of the University of NSW.

By 1947 Cotton had developed his rowing ergometer to the point where he could begin testing groups of potential oarsmen. Over three hundred were eventually assessed. A member of the 1947 Sydney University VIII, Dr Struan Robertson, recalls being submitted, along with fellow crew members, to an ergometer test on about six occasions between November 1946 and April 1947. This crew won the Oxford and Cambridge Cup for intervarsity competition, the first of three consecutive successes, all of which crews would have had input from Cotton.

In 1949 Sydney University rowing coach, Bill Thomas, approached Cotton and asked him to test a squad of potential oarsmen to help him select a crew. Cotton obliged and, on 12 February on the Nepean River at Penrith in Sydney the crew won the State Senior VIIIs title, the first time for forty years that a Sydney University crew had done this. Five members of this crew were in the gold-medal-winning VIII at the Auckland Empire Games in 1950. One of them, Ted Pain, went on to win bronze at the Helsinki Olympics with the Australian VIII.

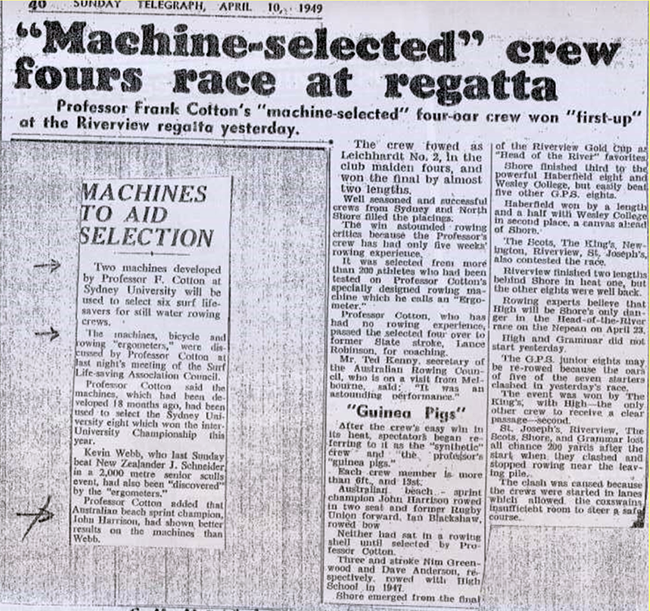

While Cotton may have been, in some ways, constrained by his academic links to Sydney University, following the success of the University VIII in the State Championships in February of 1949 he began an association with Leichhardt Rowing Club. His influence in the success of the Sydney University crew would not have escaped the notice of Sydney rowing circles generally. The ability of Cotton’s ergometer to reveal the true potential of current and prospective oarsmen led members of Leichhardt Club to volunteer for testing at the university’s physiology laboratory and were among the three hundred or so assessed. Once he had become established with several of the Leichhardt members Cotton announced that he would select a team of four “unknowns” to train at Leichhardt under former State oarsman, Lance Robinson, as coach with the aim of attempting to win the State championship. After only five weeks’ training the crew won the Maiden Fours event at the Riverview regatta on 9 April 1949 by two lengths.

The 2-man of this crew, John Harrison, was a former National beach sprint champion and had done some surfboat rowing at Newport. On a bus journey with Les Cotton, Frank Cotton’s nephew, to Sydney University where Harrison was studying Engineering, Les remarked that he, Harrison, was the very build that the Professor was promoting as perfect for rowing and suggested that he have an ergometer test. Les Cotton’s prediction was spot-on. Harrison scored well and began rowing with Leichhardt soon after. Ultimately Harrison represented his country at the Melbourne Olympics in 1956.

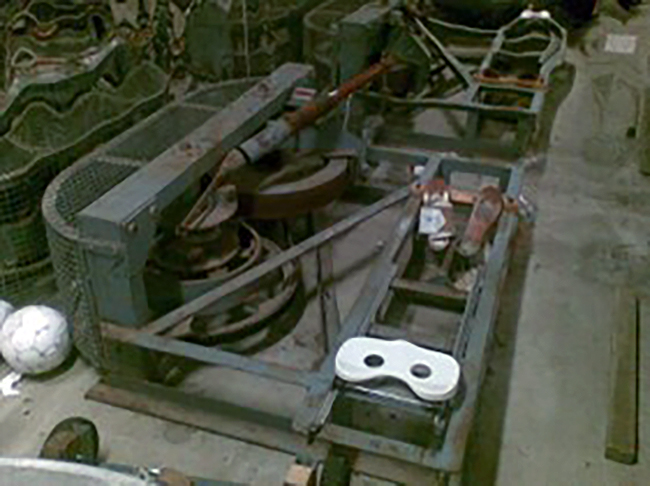

Harrison was instrumental in advancing Cotton’s ergometer design. As he was preparing his PhD on ergometer design he and fellow Leichhardt Rowing Club oarsman, Ted Curtain who ran a boiler-making and engineering business in Sydney’s West, were refining Cotton’s design and introduced a constant torque brake which increased the accuracy and reproducibility of the results obtained when rowers were under test. The new ergometer, of which about fifteen pairs were built in Curtain’s factory, found its way to the US at Harvard and Yale Universities, the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland and perhaps to Stanford University in California where Dick Lyon, US Olympic oarsman and design engineer, came into contact with it. It was from his association with the Harrison-Curtain modification of the original Cotton concept that the Gamut ergometer was developed and which has now entered, with its Gamut II model, the current phase of ergometry exemplified by the Concept II and RowPerfect machines in which the resistance is applied by air rather than a leather belt against a flywheel. In correspondence with Dick Lyon, he made it clear that his design rested heavily on the original ideas from Australia.

Back to Cotton and his Leichhardt oarsmen:

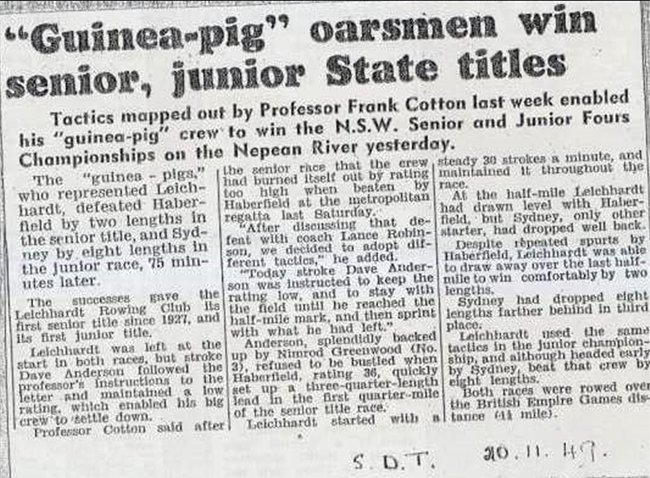

Rowing in Sydney in 1949 went into recession over Winter but, by October Cotton’s “Guinea-pigs”, as they had been dubbed by the press, were once again competing in regattas. At the Haberfield Regatta on 28 October 1949 the crew won the Junior IV race by ten lengths. Then, at the Metropolitan Regatta on 12.11.1949 the IV was beaten in the Senior IVs race but won the Junior IV event. The following week, at the State Championships on the Nepean River at Penrith, the crew won the Senior title by two lengths and 75 minutes later scored again in the Junior IVs race. It was becoming clear that Frank Cotton was onto something, his ‘guinea-pig’ crew having won two State titles on the same day in only their fourth regatta.

By now Cotton had clearly established that his scientific approach to athlete assessment, with the aid of the ergometers, was bearing fruit and was confounding the ‘experts’ who had stuck to traditional methods of selection and training. The next step for the Leichhardt IV of Harrison, Maxim, Greenwood and Anderson was to compete in the Empire Games trials set down for 3 December 1949 on Lake Wendouree in Victoria. The crew had decided to use bigger oars on the day of the test race, oars designed by crew-member John Harrison.

Dave Anderson remembers the event clearly: The big oars were not a good idea as we were beaten by Haberfield, one of whom told us later that after we had beaten them each time we had raced them in Sydney they only went to Ballarat because they had paid their expenses well in advance.

The Haberfield crew went to the 1950 Empire Games and came away with a silver medal.

During the 1950 Health Week exhibition at the Sydney Town Hall Professor Cotton’s ergometer was on display. Peter Evatt, 28-year-old son of the Leader of the Opposition in Federal Parliament was in the crowd and was encouraged to ‘have a go’ on the machine. His score impressed Cotton who persuaded him to join Leichhardt Rowing Club and enter the ‘guinea-pig’ squad. Evatt ultimately won the National Sculling championship in 1952 and represented Australia at the Vancouver Empire Games in 1954.

The VIII that represented Australia at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics contained six men who had been tested and given the nod by Cotton. Four were Leichhardt rowers; the other two were from Sydney University.

It was now now clear that Frank Cotton and his ergometer had a very important if not profound influence on the development and performance of top-level oarsmen in NSW. But it was not only in that State that the machine and the results obtained were gaining traction. The West Australian rowing fraternity had developed an interest in Cotton’s ergometer and its potential for assessment of rowers. Gordon Hill, a senior coach in WA rowing circles and one-time overseer of the WA King’s Cup VIII, wrote to Cotton on 26 February 1951 in which he discussed drawings he had of Cotton’s machine and the efforts he and his colleagues were putting in to build one for themselves.

*

John Harrison was an engineering student when he came under Cotton’s influence. He completed a PhD at what is now the University of NSW. The subject was ergometry.

In his PhD thesis, he notes that the Yale University VIII, chosen to represent the USA at the 1924 Olympics, and eventual gold medallists, were subjected to measurement on an early machine which consisted of a pump, activated by the oarsman pulling on a handle, and which forced water against a resistance. The dimensions of the various components of the pump plus the size of the resistance factor allowed the work done per full stroke to be measured. Unfortunately, the accuracy of this machine was poor and the mode of action did not represent that which the oarsman experienced in a boat. This led to Harrison joining with fellow Leichhardt oarsman, Ted Curtain, who had an engineering business in western Sydney, to develop further the concept of the lateral action ergometer based on Cotton’s prototype. Examples of this machine are to be found in the National Maritime Museum in Sydney’s Darling Harbour. Additionally, there are photographs of members of the 1972 Australian Olympic eight working on such a machine in the Sydney Rowing Club boathouse.

Harrison-Curtain ergometer photographed in the National Maritime Museum in Sydney

Two members of the 1972 Olympic VIII on ergometers at Sydney Rowing Club

Coach Alan Callaway holds the stop watch

Returning to Cotton’s progress with exercise physiology, and returning to his association with Leichhardt Rowing Club:

In spite of his war-time commitments toward the development of the ‘Anti-G suit’ Cotton continued studying exercise physiology. He had delivered a paper in Canberra during 1939 on the design and uses of the bicycle ergometer to study human work output. On 10 April 1942 he received a letter requesting details of the machine from E. R. Trethewie of the Melbourne University Department of Physiology, who had listened to Cotton delivering the paper in 1939. Cotton replied: The model of bicycle ergometer we copied was the Martin Bicycle Ergograph described in ‘Proceedings of the Physiological Society’, February 14th, 1914, page XV…

During 1949 a display was held at the Sydney Town Hall to promote Health Week. At this display, as previously mentioned, Cotton’s ergometer was exhibited and members of the public were encouraged to try the machine. The ergometer was again on display at the corresponding exhibitions in 1950 and ’51.

Having established that his ergometer was actually providing useful information, not only for his research but also for talent scouts and coaches looking for potential oarsmen, Cotton wrote, sometime during 1950, to the secretary of Leichhardt Rowing Club in Sydney regarding the potential for the club to use the machine in selection of crew members and assessment of individual’s performances as they progressed over time.

J. Beale, the rowing club secretary, wrote back to Cotton: Further to my letter of the 5th ultimo, I wish to advise that the new committee has considered your request concerning the use of your Ergometer for selection of crews.

I am pleased to advise that the Committee has decided to adopt your proposals, and the Club selector, Mr K. Bond, will contact you in the near future, to discuss arrangements with yourself.

The West Australian rowing fraternity had developed an interest in Cotton’s ergometer and its potential for assessment of rowers. Gordon Hill, a senior coach in WA rowing circles and one-time overseer of the WA King’s Cup VIII, wrote to Cotton on 26 February 1951 in which he discussed drawings he had of Cotton’s machine and the efforts he and his colleagues were putting in to build one for themselves.

In May 1953 Cotton received a letter from a J.F. Foster, Secretary of the Associations of Universities of the British Commonwealth who had been involved in organising a meeting of the Society of visiting Scientists. During this meeting there was a section set aside for a discussion titled ‘The Physiology of Athletics’. Although Cotton did not attend this London meeting it is apparent that Foster, who had met with Cotton previously, had become enthused about Cotton’s investigations and had discussed them with scientists in the field in Britain. In his letter to Cotton Foster had the following to say: I have dined out a good deal since our conversation last year on the stories you told me about the selection of athletes generally, particularly oarsmen. …. I have found that a good many University people are very interested in what I told them of your influence on the selection of crews in Australia and of the fact that you have shown that un-trained oarsmen, if properly selected, can beat the orthodox champions, but some are frankly incredulous and ask for chapter and verse about the New South Wales and Australian crews.

The fame of the ergometer even penetrated as far as this genial northern State. On 16 March 1955 David Kronfeld, a lecturer in physiology at the University of Queensland, wrote to Cotton after the latter had paid a visit to Brisbane. He said: Your visit to Brisbane has certainly ‘driven the legs down hard’ in Brisbane rowing. The impetus to the sport has been amazing. It has been in the right direction for the men are now becoming interested in the ways science can help in the selection, training and coaching of crews.

He goes on to say, with regard to the best effort that can be made to progress rowing in Queensland: … something useful, directly beneficial to the sport. What is this thing we can do? Get your machine!

You remember I tried alone once before in 1951. Now after your visit everyone wants it.

It was sometime during 1949 that Cotton decided it was the moment to put his theory of selection of oarsmen to the test. By then his squad had become known both in rowing circles and the press as ‘Cotton’s guinea-pigs’. In his notes he has listed a regatta program entitled “A Programme for Guinea-Pigs”. It was as follows

REGATTA - COURSE - EVENT

Mosman 1.10.49 - Lane Cove - Maiden VIII – 1 mile

Glebe 15.10.49 - Iron Cove - Maiden VIII Jnr IV

Haberfield 29.10.49 - Iron Cove - Jnr IV (1 mile)

3.10.49 - Iron Cove - Test race for use of Club’s Best & best IV

Metropolitan 12.11.49 - Parramatta R. - Snr IV 2000m

Nepean 19.11.49 - Nepean R. - NSW Champs 2000m

Sydney 26.11.49 - Parramatta R. - Snr IV 1 mile

Ballarat 3.12.49 - Lake Wendouree - British Empire Games Test IVs 2000m

LIST OF OARSMEN

- J. Harrison

- D. Anderson

- N. Greenwood

- J. Maxim

- G. Williamson

- M. Finlay

- J. Hurst

- P. Bayliss

- P. Musgrove

- K. Goddard

- H. Rummery

- P. Evatt

- B. Hessian

- J. McLeod

- P. McGrath

Having established his group at Leichhardt Rowing club, Cotton oversaw their training and their entry into competition. Below are two newspaper reports of their results.

Plaque on the wall of Cotton's former laboratory at the Anderson Stuart Building, University of Sydney

A final anecdote

Cotton was scrupulous in his avoiding the giving of off-the-cuff advice on training to aspiring athletes who had heard of his methods. Right up until the time of his death he was receiving (and replying to) letters from all over Australia from sporting and athletic hopefuls who were asking for his advice on training regimes. In early 1955 a letter came from a Perth schoolboy who, having described himself as an aspiring 880 yards and mile runner, asked Cotton for advice on how to set up a training plan. As he always did with enquiries from unknowns, Cotton replied that he didn’t set up schedules for athletes with whom he did not have direct contact. He wished the lad all the best, advising him at the end of his letter to establish himself with a coach and a schedule and he would most likely progress.

The lad was Herb Elliott.

Information producing the story was discovered while researching the Cotton archives at the University of Sydney’s Fisher Library.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Lise Mellor, University of Sydney Medical Foundation.

- Professor Roger Dampney, Department of Physiology, University of Sydney.

- Dr Tim Robinson, Senior Archivist, University of Sydney.

- National Maritime Museum, Sydney, and Sport & Leisure History curator Penny Cuthbert.

- Emeritius Professor David Anderson, University of Wollongong.

- Andrew Guerin & 'Australian Rowing History'.

- Forbes Carlile.

- Harry Gordon, author of "Australia at the Olympic Games"

- ABC Radio National "The Sports Factor"

- ABC TV and Mr Peter Thompson, 'Talking Heads. "

- Pam Chambers, Professor Cotton 's grand-niece.

- Dick Lyon, ex-US Olympic oarsman and developer of the Gamut ergometer.

- Dr Struan Robertson, Sydney University Rowing Blue and Cotton subject.

- Dr Peter Musgrove, Sydney University Rowing Blue and Cotton subject.

- Robin Poke, journalist and author of biography of oarsman Peter Antonie.

- The State Library of NSW

- The National Library of Austrafia and 'Trove', their on-line newspaper access.

- Professor David Bishop

- Emeritus Professor John Harrison and his daughter Lorna.

- Leichhardt Rowing Club and the Club 's historian Merle Kavanagh

- Sydney Rowing Club, club historian the late Alan May and current Club President Keith Jamieson

- Shore School archives and archivist, Kate Risely.

- E R Curtain & Company

And anyone I've forgotten

A number of these oarsmen went on to international success. Below is the make-up of the bronze-medal-winning Australian eight at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics.

1952 OLYMPIC GAMES Men's Eight – Bronze

- Bow: Robert N Tinning (NSW)

- 2: Ernest W Chapman (NSW)

- 3: Nimrod Greenwood (NSW)

- 4: David R Anderson (NSW)

- 5: Geoff Williamson (NSW)

- 6: Mervyn D Finlay (NSW)

- 7: Edward O G Pain (NSW)

- Str: Phillip A Cayzer (NSW)

- Cox: Thomas E M Chessel (NSW)

In this crew are four of Cotton’s recruits: Tinning, Greenwood, Anderson and Williamson.

*

Ian Stewart

January 2024