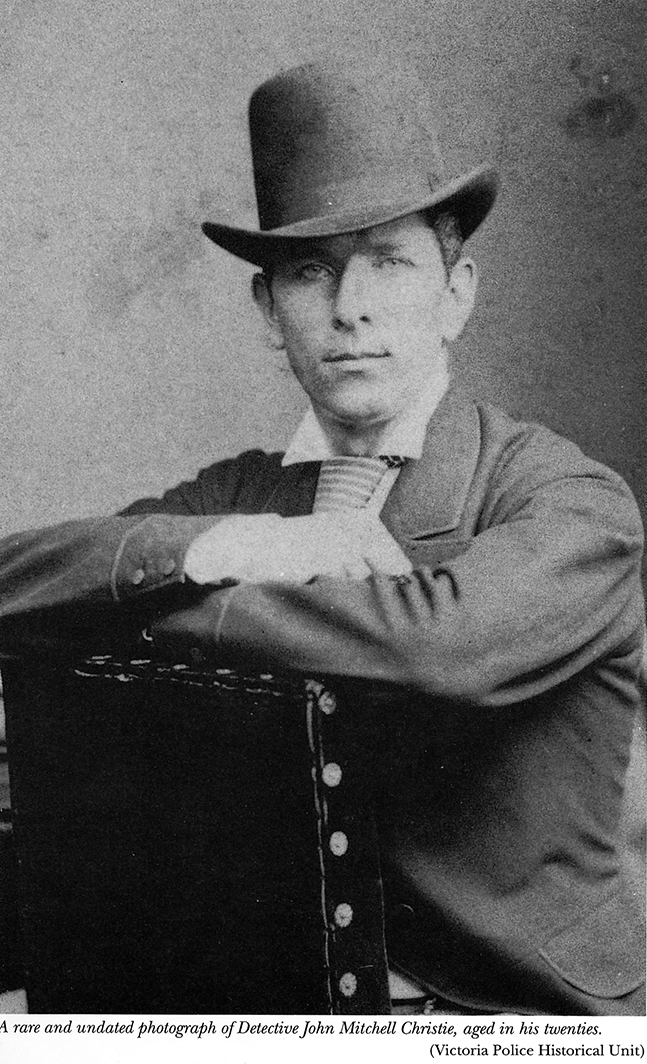

John M Christie

John M Christie

I Zingari Rowing Club (VIC)

Born about 1845. Died 11 Jan 1927, aged 81 years.

Some rowers, whilst also champions, led far more interesting lives outside the sport than within. One such person was John Mitchell Christie.

The following information is extracted from a book written by John Lahey in 1993 and published by the State Library of Victoria and titled: Damn you, John Christie! The public life of Australia’s Sherlock Holmes.

Born in Scotland in about 1845, he migrated to Australia. He joined the detective force in 1867 by walking in off the street with a character reference. This was a normal way to do things at that time. You did not need to be in the police force first.

Christie turned out to be a daring, brash, resourceful, innovative, tough and uncompromising detective in early Melbourne, who had much success. He was chosen as the body guard of the Duke of Edinburgh on two occasions when the Duke was visiting Australia and was invited to join the Royal guard permanently.

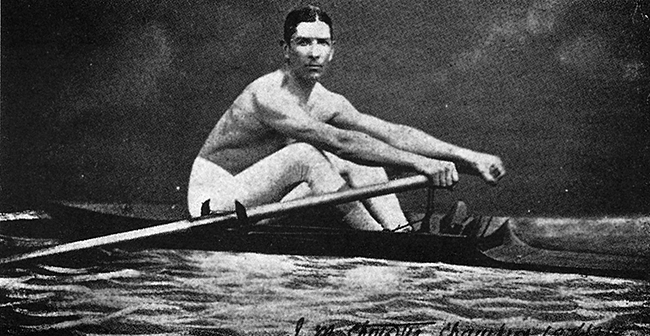

He was also a sculler and boxer of some repute. John Lang’s The Victorian Oarsman notes Christie as the amateur champion sculler for the “Australasian” Cup in 1876 and 1877. He also won the senior sculls at the Barwon Regatta in 1877. Interestingly, we have not found any other early races which demonstrate how he obtained this skill.

Lahey in his book reports that in 1875, Christie issued a challenge to all scullers in Australia to race an outrigger sculling match over 2 mile and offered a gold cup to the value of £100 to the winner. The controversy about the event was that he chose to name it a Championship. This naturally angered the Melbourne Regatta Committee which was the authoritative rowing body in Victoria at that time. Christie had clearly snubbed the system.

Noted Victorian sculler James Cazaly from Melbourne Rowing Club took up the challenge on the Lower Yarra. I quote from Lahey: Christie and Cazaly were described as “two of the best, if not the very best rowers in the colony”, and so the match created much public interest. When the two of them got to a point called Humbug Reach, Cazaly steered too close to the Sandridge (Port Melbourne) bank, gave himself trouble in making a turn, and yielded the lead to Christie. Then Christie got his left hand caught in reeds growing from the bank, and was yanked into the water. The race had been so furious that spectators thought he had fallen in from exhaustion, and one jumped in to save him. Christie held onto the lead to the end, rowing desperately. Christie's time of l0 minutes 12 seconds, over a course that was not quite two miles, established him as probably the fastest Melbourne sculler in his day.

In his book, Lahey relates a story which combines both his rowing and boxing expertise.

The story grew that Christie left the detective force because he wanted to concentrate on sport, and this was a reasonable explanation to the public, because he continued to scull with great success, and he opened an athletics hall, or gymnasium, in Little Collins Street, where he taught boxing and kept in trim for his own bouts.

The old dare-devil Christie showed as a detective, remained with him. Training as a sculler one day on the lower Yarra, he was hit hard between the bare shoulder blades by a rock thrown at him from the bank, and he bled profusely. In a weakened state, he pulled in and asked some workmen to catch his attacker, who was running away. When they brought the man back, Christie recognised him as John Sharp, a burglar whom he had put away in 1868 for robbing the mayor's house. "Well, Sharp," said Christie, "if you had hit me on the head instead of the back, you would have finished me. But if you will stand up and face me for four rounds, I will cry quits."

God knows why Sharp agreed to this, but he did, and the workmen formed a ring. Sharp faced a known, skilful, athletic, angry, bare-knuckle veteran capable of inflicting terrible punishment and staying on his feet for 30 rounds or more. Four rounds were nothing to Christie. But perhaps a beating by anyone was preferable to another spell in Pentridge. In any case, Christie won, and he was to say later that he had never settled with anyone so cheerfully as he did with Sharp.

After such an incident, other men in Christie's place might have said to the workmen, 'Thank you, lads, I owe you a favour." Christie's gestures were more dramatic. He invited the foreman and a dozen of the men to the nearby Admiral Hotel, on the corner of Collins and King Streets, to drink his health. Twenty-two turned up. One can imagine them trooping excitedly up the street after him, talking about this punch or that. Other men might have bought them one drink each, then said goodbye. Christie stayed to buy them all a second.

Christie trained hard at his sculling. Melbourne people, favoured with two rivers, the Yarra and the Saltwater, had been familiar with water sport since the first regatta in 1841. By Christie's day, rowing ranked with football and cricket as one of only three sports which attracted big crowds; and now it was entering a great era, for in 1876 various oarsmen founded the Victorian Rowing Association, which is said to be the oldest of its kind in the world. It took over the Melbourne Regatta and for the first time provided a body to regulate all other rowing competition. This period coincided with Christie's new freedom to train and perform.

In 1876 he won the Victorian amateur sculling championship the real one - competing against John and James Cazaly and P. J. Carter. Christie started as favourite and led by 100 yards before half-way. John Cazaly, who came second, made a late surge, but could not catch him. In the following year, Christie retained the championship against James Cazaly and W. Stout. But he was 32 by then - old for a rower - and when he was beaten in 1878, he readily acknowledged that his opponent was better, and bowed out. He did little competition rowing after that.

Christie in 1876 as Champion

Christie joined the Customs Department and rose to the rank of Detective Inspector, reaping the Colony vast amounts of money with his strict and uncompromising approach. He was one of the great sportsmen and detectives and clearly one of the great characters of early Melbourne.

Compiled by Andrew Guerin from John Lahey's book, Damn you, John Christie! The public life of Australia’s Sherlock Holmes.

December 2018